ARToba Artist in Residence

Residency #1: Marlene LAHMER

Residency Period: 29 Nov – 2 Dec 2024

Location: Ohama Studio, Ohama-cho, Toba city, Mie Prefecture, Japan

Photo: OHNO Aiko and Marlene LAHMER at Toba Sea-Folk Museum

Marlene LAHMER

Marlene Lahmer (*1996, AT) is a feminist artist and writer. Her practice contains installation, performance, sculptural approaches to glass, and text. With these tools, she examines, for example: What does glassmaking tell us about the conditions of our environment and our precarity in it? What shapes our fragile understandings of intimacy and gender? How can (auto)biography and fiction intersect to form emancipatory narratives? Material-based, lyrical and theory-informed approaches overlap translucently, incongruently and sometimes complementarily.

Marlene is part of the art-activist collective Elsa Plainacher and publishes poems and articles. She graduated from TransArts and English and American Studies in Vienna (AT) and did Erasmus in Glass Art in Estonia. She is currently researching feminist art practices and heat at the University of Arts Linz (AT).

Residency Report by Marlene LAHMER

This report combines how I got to know of Toba, my experiences here, and the thoughts they sparked.

INTRO

I am currently (9 Sep – 6 Dec 2024) in Japan for an artist-in-residence at Joshibi University of Art and Design, a women’s university in Sagamihara, Kanagawa prefecture, near Tokyo.

In the first days of my Joshibi residency, I met Linda Dennis, who teaches at the International Art and Culture major. Over lunch, she told me about the student projects she had been running in Toba in collaboration with Ama divers, gifted me the project report book of “Ama Divers & Craft“ (2023), and extended an invitation to come visit and stay at her studio.

Now that my time in Japan is almost over, I had the chance to come here for 4 days to research about the female* tradition of the Ama divers, gather some more inspiration for my PhD project (which is a project situated between art practice, fiction writing, and cultural studies; the connection to the Ama divers is that my project also treats female* work and life communities), and reflect on my recent activities. The Toba resicency is a residency within a residency, so to say. 😉

Linda has remotely organized for Aiko OHNO, her friend and collaboration partner who is a photographer and has been an ama diver in Toba for the past 10 years, to pick me up and get me settled.

Photo: Linda DENNIS and Marlene LAHMER at Joshibi University of Art and Design, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan

_________

FRIDAY

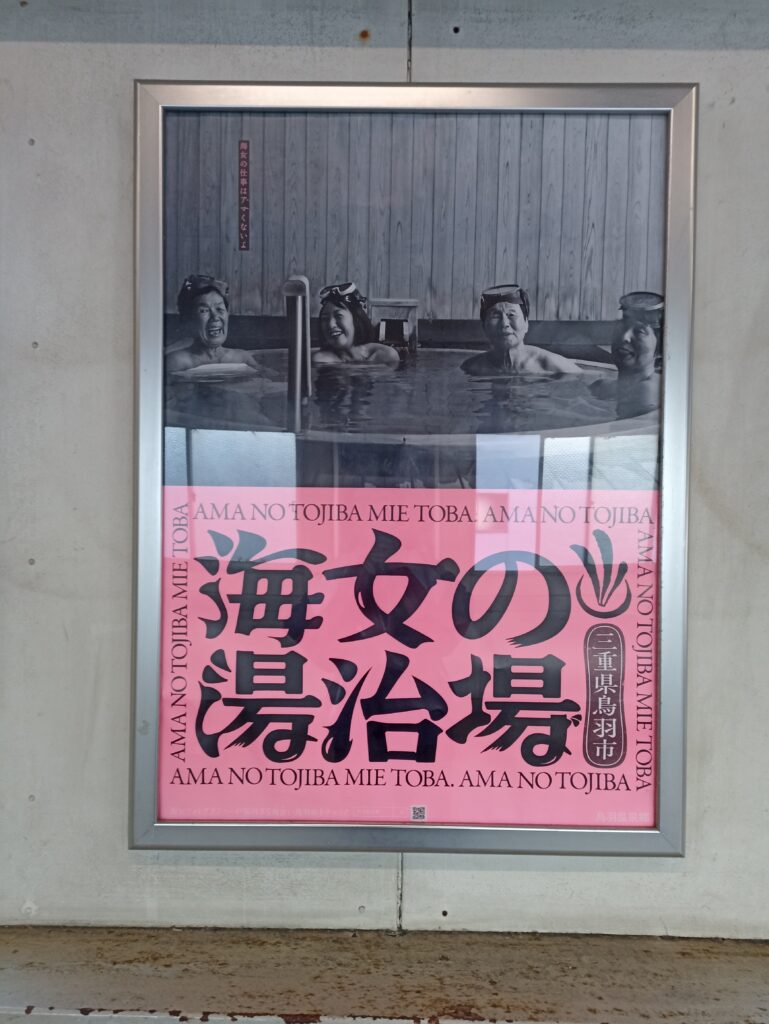

I arrive by train. Before I meet Aiko, her photograph featured in a poster already greets me at the station. It is a sunny winter day. I walk around the station area, check out the Toba Marche market stands and sit down at the Marine Terminal to look at the sea.

Aiko texts me, her work for the day has finished and she awaits me at Yumin Kaito Club (?), a tourist office run by her friend that organizes eco tours in the Ise National Park, which Toba is part of. I pick some information brochures and Aiko’s friend hands me her illustrated map of her home island Toshijima, which belongs to Toba and is just a 15 min ferry ride away.

Aiko and I sit down and introduce ourselves. Aiko tells me of her work as an Ama, her life in Toba and the time before, when she had lived in Tokyo, first as a marine biologist and then as a photographer. I tell her of my artwork, mention that I’m also an English teacher and show her two of my breast imprint glass sculptures that I made at Joshibi and brought with me to Toba.

I ask for the differences between urban and rural life. Aiko tells me that she does not listen to music anymore but to the birds and waves instead and that she cherishes the starry night sky and the view of the ocean. I tell her that my family comes from a region at the river Danube in Austria and that I, too, appreciate the water.

Aiko tells me of an ama diver show at Mikimoto Pearl Island, “But it’s only a show“. She wants to depict the ama divers in a truer to live and contemporary way. “We do not wear white clothing today, we wear wetsuits to protect us from the cold and from getting scratched. “

I show Aiko the little weathervane made from my grandma’s handkerchief that I want to install at Linda’s studio.

Aiko drives me to Hello Plaza for grocery shopping and then to Linda’s studio in Ohama. As we arrive, the I. family (I use abbreviations because I did not ask their consent to be named here) who lives across the street also arrives from their week on Kamishima Island to spend the weekend at their Ohama home. They have their pet rabbit ‘Nuts’ with them. I bond with the children (R. is 5 years old, Y. is 14) over the fact that I have rabbit, too. Y. has written an English essay about her home island Kamishima for a speech competition. She shows it to me, we go through it together.

Aiko checks out Linda’s studio with me, we agree to meet the next day for lunch and a visit to the Toba Sea Folk Museum. I take time to get familiar with the place and get cozy next to a window with ocean view. I eat, go through my brochures and rest wrapped in a blanket on the tatami floor. The past weeks have been intense, artistically and socially. I navigate between the deep gratitude for the chance to focus exclusively on artmaking, researching and student/lecture activities for the past three months and my tendency to get overinvolved and thus overwhelmed. At night, I take a short walk to look at the stars.

Photo: Marlene LAHMER at Toba Station

Photo: Poster at Toba Station

Photo: Ohama Studio Entrance

___________

SATURDAY

It’s 8am, I just got out of my futon bed, and the doorbell rings. I think I must have imagined it, but it rings again. It’s Y. and her mother who bring me a tray with breakfast. On it, there are two onigiri made from rice that her grandparents grow in Toba, a cup of hot broth, some Japanese sweets and souvenirs, and a letter that asks me to spend time together again. After I have finished this heartwarming breakfast, done my morning Yoga, and got dressed, the I. family have already left the house. I leave the tray at their entrance and add a persimmon, a biscuit and a note saying I will be back tonight and am happy to practice English with Y. again.

Photo: View from window on the upper floor of Ohama Studio

I pump up the tires of the white bicycle and leave for Toba city. Having a bicycle always makes me feel more local in a place. On the short ride I pass by fisher people and hotel staff and marvel at the coastline. I turn left after Toba Marche and ride down the promenade a little. Then I check my “Toba off the beaten track” map. It suggests the SYM Sea Lounge, a place for coffee and simple meals above the Marine Terminal, with a view to the ocean. I long for that, so I head there. I don’t find the entrance right away and try several locked doors in the glass front – I have already sparked the curiosity of the visitors sitting at the counter. They ask me where I’m from – “Austria-no desu. Europe. Below Germany”. I order hot coffee. An elderly man engages in a short English conversation with me. I choose a table with a good view of the ocean but is close enough to the counter, so I don’t cut the connection to their community.

I have an itch to write, not knowing yet if it will be something personal or artistic that I must negotiate with my notebook, or as often a mix of both. At 12, I pay for my two cups of coffee. I discover a large, roofed bike shed at the back entrance of the Marine Terminal. I lock the bike there and walk to Toba Bus Center to head for the Toba Sea Folk Museum. At the bus center, I notice there is a direct bus to the Ise Shrine (Geku Jingu) – maybe I will visit it on my way back to Kanagawa.

It is Saturday and the bus schedule on weekends is different than the one I got, so I have some more time to wait and roam around the station area a little. The 40min bus takes me along the coastal road. When I get there, Aiko has not arrived yet. The museum staff greet me, they have heard of my visit already and show me a short film about the Ama divers in Toba. The piece of information that sticks to my head most is the fact that the divers only started wearing the white clothes that can be seen in many of the folkloristic-looking depictions after photographers had come to take pictures of them in the early 20th century. To protect their bodies from the on-lookers. Previously they had been diving naked.

Aiko and I have oyster curry at the museum cafe. There is a sheet on the table showing illustrations of different types of seaweeds. Aiko tells me which one she harvests, how they are prepared and that they have many vitamins that are good for us vegetarians. By the way, I find it interesting that Aiko uses the word “harvest” to refer to her catch. In the film, they called it prey. The ama dive for shellfish as well as seaweed, so technically both terms are applicable, but harvest has a much more peaceful connotation that reminds me of cultivation. The ama have not cultivated what the sea provides, but they take care to keep the population stable, by measuring abalone shellfish and throwing the ones shorter than 10.6cm back into the sea.

Photo: Toba Sea-Folk Museum

I order tokoroten for dessert, an algae jelly with with soy flour – oishi. Aiko gifts me a postcard of her previous exhibition that shows two elderly ama in the sea. “What a great photograph, with the blurry sea splashing in the foreground.” – “The sea is a creature of its own. The divers are already over 80. I don’t know if I’ll be able to dive that long, but I’ll do my best. This photograph is important because it shows one ama who has died at sea.” – “I’ve read of it, in Linda’s book about the craft project. You say that it happened the day before the students arrived.“ “Yes … but I’m happy for her, she really loved the sea and I think she was happy to die at sea.“ – “So she became part of the sea.“ – “She was my team member and when I go diving, I feel she is still there and watches over us.“ – “What was her name?“ – “Tora. It means tiger.”

We enter the museum building, the staff let me enter for free, since I’m a researcher. The complex comprises two wooden buildings somewhat resembles an upside-down boat and has glass windows along the highest point of the roof where daylight enters. It is designed by the famous Japanese architect NAITO Hiroshi. Between the buildings is a grey stone garden with an installation of boat-like oxidised copper disks. I feel it elegantly talks about how differences of moving and dwelling on land and on sea: of weight, floating, gravity, friction. And though it conveys a spatial perception of being at sea, it also makes clear that the laws of the sea cannot be fully transferred to land (but have to be felt to be understood).

In the ama section, Aiko shows me how to recognize the different types of abalone and how to use the knife to get them off the rock. Holding them between her fingers, she can bring up to 4 abalone weighing up to 2kg to the surface at a time.

I check out the depictions of the ama because I find it special to see a record of so many female* professionals at a time, working together. In almost all the photographs, they are laughing. I come from a cultural background in which we are used to seeing historical images of men* doing the physically tough and adventurous work and of women doing housework, social work, and especially textile work. Of course, we have long understood that this does not mean women never did tough or adventurous work, but that the historical gaze has had an interest not to show this to us. When we look at archives, we sense this gap in the record and try to imagine what it might have been like. This undertaking is often referred to as speculative history. My friend and fellow artist Marlene Fröhlich is doing an extensive project of prompting AI image generators to create photographs of imagined scenes of women* and queer communities from the past. Some of them are similar to the bold and un-self-conscious depiction of the laughing Ama. I think, “Marlene (referring not to me, but my friend), these images already exist, they have just been placed outside of our reach.”

There are not only photos of the ama, but depictions in Japanese paintings, illustrations and toy statuettes ranging from the previous century to the present day. In one painting, the ama look just like people doing their thing, carrying a knife in mouth, wringing hair, catching an octopus; in another, they look more like the nymphs I’m used to seeing in Roman and Greek depictions – mystified and somewhat sexualised tender females, watched from the perspectives of a voyeur. One poster shows a very young diver in her face mask and a short white cloth. She looks incredibly docile, shy, and pleasing. Such depictions of women* cause an almost bodily reaction in my that makes me want to cast off my skin, to cast off the male gaze that wants to see me that way. My installation “source of heat” presented at Joshibi refers to that too – in a photograph, I staged myself as a godess-like figure sitting on a glowing hot glass furnace (to be read as an extension of my vagina), wearing a glass bra on my otherwise naked breasts, facing the viewer with a no-bullshit expression. It says: I’m not here to pleasure and serve you, my energies can burn you.

Later, Aiko and I talk of the importance of her being not an outside observer but one of the ama divers who takes the pictures. “Did you take photographs of the ama from the start?” – “Usually, ama divers hate having their pictures taken. They would not allow it from a stranger. When I came here, I thought it was important to focus on becoming an ama diver [earlier, Aiko had told me how much effort and exchange with more experienced divers it took her to understand where to find abalone and how cut them without injuring them]. Only after two, three years I asked to take photographs of my co-workers. And they were like »Of course, you can take pictures of us. What is important is the connection before you take the pictures.”

(I think of the Estonian filmmaker Anna Hints, who has regularly visited the sauna with a group of women for 7 years before making her empathetic, intimate and brutally honest documentary “Smoke Saune Sisterhood“.)

Aiko and I say goodbye at the Marine Terminal, tomorrow will be a clear day and she will be harvesting again. I ride home and knock the I. family’s door to let them know I’m available for a conversation session. They tell me than R. is at his Taiko drum lesson at that moment and that we can go together to watch and try. The teacher welcomes us to join the practice. She shows us the right posture, positions of hands and how to hit the skin to cause a vibration. I realize that Taiko involves the whole body, not just the hands. As we go home, I tell the family about my artwork and offer to show them my glass sculptures later. After dinner, I knock their door again. They invite me in for cake and tea. We talk of glasswork, my life in Austria, their life in Toba. I hand them my sculptures to touch. The rabbit is also there, in his cage in the other room. R. sings “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” and Y. teaches me the Japanese word for star: hoshi. I show pictures of Sachertorte (a Viennese cake), dance a Waltz with Y. and tell her that we dance it on New Year’s Eve when the clock strikes midnight. They tell me of their hikes to Mt. Fuji, the limestone cliffs of Kamishima and that on clear days they can see Mt. Fuji from there. I tell them of the heavy floods in Austria this fall and they show me pictures of Noto peninsula, Ishikawa prefecture, where they volunteered to clean the debris after the catastrophic earthquake in the beginning of the year. It’s almost 10pm when we say goodnight.

_________

SUNDAY

I set my alarm early to see how the sunlight changes over the ocean at dawn. The magic basically happens between 7 and 7:15. I get ready to visit Toshijima island today. As I open the front door, the I. family is just leaving the house for a trip to the zoo. We take a picture together in front of Ohama port.

I cycle to Toba Marine Terminal and take the ferry to Wagu, the second largest village on Toshijima. I collect shells and shards. At small sunny beach I decide to go for a 1st-of-December swim. There is only one other couple in the distance. I change into my bikini. (I love winter swimming ever since I lived in Estonia seven years ago.) I think of Aiko who is in the ocean today, too. The water is not that cold. Seaweed grows abundantly on the rocks below me. I swim beyond the small bay where I entered the water. As I turn to swim back, I think for a moment that I’m not getting ahead because the pull of the tide is quite strong. No worries, I’m a good swimmer and with a few strong fast movements I get closer to the shore again. But I recommend being careful there.

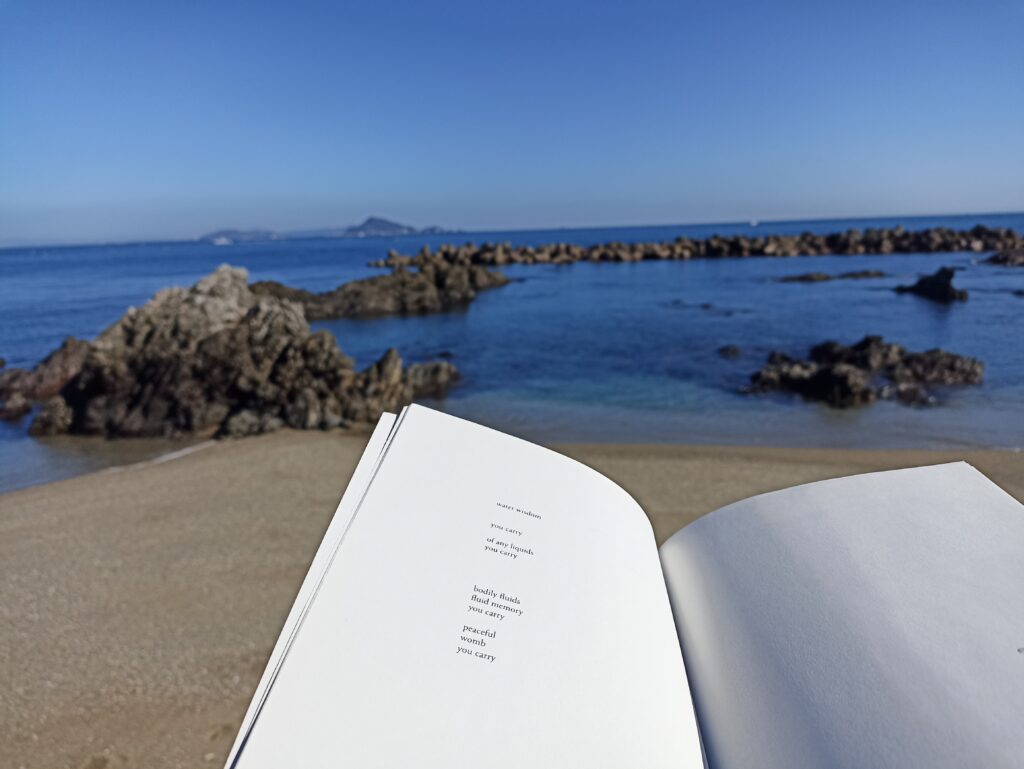

Photo: Beach on Toshijima

At the beach I warm myself on a rock in the sun like a snake. I take out “Water’s Skin“, a poetry book by my colleague Ava Binta Giallo. I brought it because I thought Toba might be a suitable place to re-read it. Binta is an artist who lives between Vienna and Capo Verde, with roots in Germany and Guinea. In “Water’s Skin”, Binta negotiates un-remembered memory and ancestral knowledge that lives in the body through the figures of bodily fluids and water. After all, water is a great connector, as source of live and of insecurity. Binta refers to various authors who write about displacement and/or Black indigenous philosophical traditions. Elements like water, clay, sand, soil and recently glass form part of their sculptures and installations. (I by the way absolutely recommend Binta as a future artist-in-residence, I think they would be a great fit.)

The sound of the waves envelopes me, makes me tired. I close my eyes, doze off. I almost lose balance on my rock. A sign to continue my way. (I want to continue to Toshi village.) I don’t know if it is the smell of food or the sound of people chatting, I first perceive. The wooden slide door of the small restaurant is closed (Linda has told me it might be difficult for me to recognize if a place is open), but the black board outside shows a fish drawing and a price next to it, so I enter. It is a sushi place; I order a set and hot sake and get green tea to warm myself. The owners, a man-woman-couple, are surprised by my swim – “samui“ (cold) – tell me they are divers too. The woman is an ama and the man is a kaichi. But they only dive in summer. The woman is named Katsuyo, she tells about the famous sawara mackrel from Toshijima and offers to take me to the fish market. She greets the fishermen and women, tells me there are many old fishermen but only a few young ones. They are weighing sawara and other fish and putting them in boxes. Soon the auction will start. The bidders arrive. One man has prepared a white board, a woman holds a pen and a folder – the auction managers. The bidders huddle around the boxes of fish. Each of them has a flat black stick that is about 15cm long and has a kanji written on it. When the auction manager calls out, they write their bidding on it with chalk. The highest bidder gets the fish and the boxes are swiftly packed for them. No time to snooze, every chalk line is fast and precise. The boxes quickly disappear on the landings of the bidders’ pick-up trucks. Katsuyo explains that the most valuable sawara are the ones with over 10% body fat. It is measured with a hand-held device whose metal knobs just touch the skin of the fish to determine the percentage (x-ray, ultra-ray? even though my father is a doctor I do not know which rays detect fatty tissue). The best sawara are marked with a tag around the fin. We stay until the end of the auction and watch the bidders drive off and some of the fisher people go back to sea. Katsuyo walks me to a small museum in Wagu. We briefly talk with women who work there. I tell them about my art residency and show the Toba Stories Art Project to them on instagram.

My ferry back to the mainland leaves at 4pm. Back at Toba Marine Terminal, I have another coffee (at the SYM Lounge that is about to close for the day) and buy a postcard with an illustration of an ama diver. I think it’s a good complement to the postcard Aiko gave me the previous day. Coincidentally I meet the I. family again, they are about to depart to Kamishima for the week. They show me Kamishima, a triangle at the horizon. I tell them that I saw Kamishima from Toshijima today when I had my swim (Kamishima is the island farthest away from the mainland of the five municipal islands belonging to Toba). I walk to the terminal with them and wave them off. R.‘s “see you“ still sounds over the water as the ferry is leaving the port. I’m impressed and humbled by the openness and kindness of this family. Their joy in our interaction feels very genuine. I watch them until their ferry is just a light dot approaching the triangle. As I turn into Linda’s street, I hear someone laugh on a boat off the pier. It sounds so close. Curious how the water carries sound.

This evening I walk up the hill to visit the onsen at the hotel. The atmosphere at the bath is a bit hectic, people talk quite loudly, ordering their children around. I prefer my very unfancy sento in Sagamihara, I think to myself. The outside pools face the ocean and just below there is crane in the water who makes the scenery almost too kitschy. I wonder what it has been promised to stay there.

On the way down, I look at the stars. One last night sky in Toba before I depart. When I find the Venus, I always have to think of my friend’s son who showed it to me on a night walk once, telling me it was the brightest of all stars. There are three stars unusually close to each other that I don’t recognize. I wonder how my current perspective of the stars differs from the one in Central Europe.

_________

MONDAY

I feel it is time to gather my impressions instead of searching for new ones. My PhD supervisor has used the very fitting German word “einhegen“ to describe the gathering/grouping-together and making sense of disparate content. I cannot translate it, but what it connotes to me is the image of kneading dough.

I take photographs, find a place for my weathervane and leave a note.

Two last morning coffees at SYM Lounge, I try unknown seafood at Sazae Street next to the station, kimo shellfish looks like a snake or tentacle with a slightly psychedelic pattern of concentric circles. I can’t place the taste.

I go to Mikimoto Pearl Island. Aiko’s mention of the unauthentic Ama show has made me curious. After the diving performance at sea, I follow the Ama boat and take pictures of the performers coming back to land.

I pay a visit to the Naiku sanctuary in Ise on my way back.

Photo: Ama Diving Demonstration at Mikimoto Pearl Island

_________

Foot Note:

I always use * behind the words “female“ or “male“ to signify that I speak of gender as a cultural category, not an essential or biological category. I do not believe in a two-gender system because it is too rigid to allow for the plethora of all our (gender) expressions. I believe that identification with the terms “female“ or “male“ is a free choice and may be fluid or temporary.

Useful Information:

– The onsen (hot spring bath) at the hotel near Linda’s studio is open until 12 midnight. The ticket is 1200 Yen.

– The bus from Toba Bus Center to the Toba Sea Folk Museum has a different timetable on weekends (ticket 500 Yen, 40 min).

– There is a direct bus from Toba Bus Center to Naiku and Geku sanctuary of the Ise Grand Shrine (approx. 40 min to Naiku, ticket 910 Yen).

– Toba Bus Center also has coin lockers.

– At the back entrance of the Toba Marine Terminal, there is a roofed bicycle parking area.

– Next to Toba Bus Center there is a bike rental business that has facilities with a bicycle pump etc.